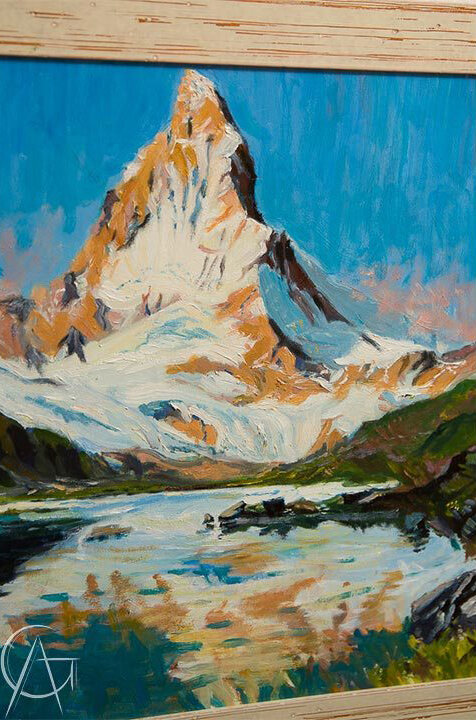

People often ask me why I return so often to paint the Matterhorn? Well the answer is both simple and complex.

As a climber and Mountain Guide the Matterhorn has long been a focus and inspiration. When, as a young climber, I first came to the Alps, its iconic shape was an hypnotic challenge and a summit I realised early in my climbing career. More than half a century later and after numerous ascents, my passion for this most iconic mountain has never wained. If anything, the more time I spend in high places the more my passion for them increases as does the intensity of the emotions I experience. Simply put, the mountains of the Alps and all natural landscape are a source of Sublime Inspiration for me, both as artist/painter and climber.

But there is much more to the Matterhorn. Even the story of its first ascent in 1865 by Edward Whymper and his large team of fellow climbers and Guides was both momentous and tragic. In itself, the ascent of the Matterhorn marked the end of the Golden Age of Alpine mountaineering. It was the last of the great summits to be reached. Tragic, because on the descent, after a slip and a broken rope three of the climbers fell to their deaths. Resulting in Queen Victoria herself asking her Prime Minister to see if the burgeoning pastime of Alpinism could be banned?

No matter how ofter I return, seeing the Matterhorn is always a shock to the creative imagination. But the mountain holds another secret unfolded only by geologists. The Matterhorn, the most quintessential of Alpine mountains and a Swiss gem, is in fact, part of Africa? As the tectonic plates of Europe, Asia and Africa collided to uplift and create the Alps a part of the African plate slid over the European plate and forms the main pyramid of the mountain, itself sculpted and shaped by weather, time and glaciers.